MSc Psychology - Advanced research project

School of Psychology, University of Kent

Project supervisor: Dr Francesca Carbone

Final grade: Distinction

Please note: The following is an accessible summary of my original study. Its purpose is to give non-experts an opportunity to dive into my investigation of psychology and creativity. The original academic version is available for download.

Fantasy versus Reality Content in Films – The Impact on Creativity Outcomes in Adults and Children

Keywords: Creativity, Fantasy films, Divergent thinking, Narrative transportation, Openness to experience

Denslow, W. W. (1900). [Illustration]. In L. F. Baum, The Wonderful Wizard of Oz (p. 25). Geo. M. Hill Co.

“Toto, I’ve a feeling we’re not in Kansas anymore.” (Vidor et al., 1939)

With these words, Dorothy steps from sepia-toned Kansas into the technicolour dreamscape of Oz, marking a cinematic moment where reality and fantasy blur. Despite its cultural prominence, surprisingly little is known about how watching fantasy films affects creativity. As filmmaking becomes increasingly immersive, psychologists are beginning to question whether fantasy content can help or hinder creative thinking.

Part One: Literature review

Until the mid-20th century, creativity was largely neglected by psychologists.

J.P. Guilford (1950) argued that creativity had been too long ignored in psychology, despite its importance in science, education, and daily problem-solving. He described creativity as divergent thinking. This means the ability to generate many original ideas, supported by fluency, flexibility, and elaboration.

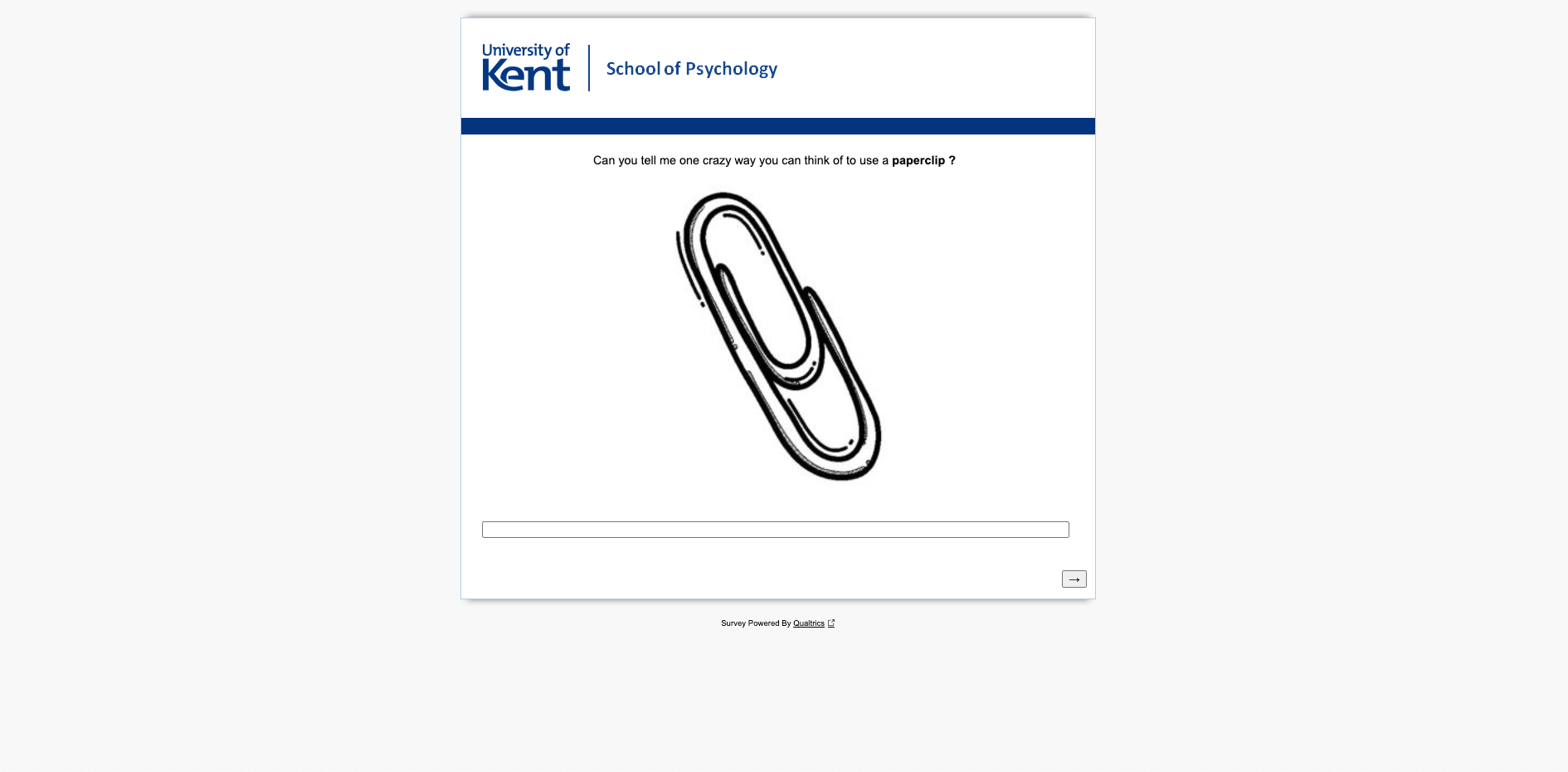

One of the most widely used measures of divergent thinking is the Alternative Uses Task (AUT) (Guilford, 1967), in which participants think of unusual uses for common objects, such as a paperclip or a shoe.

Later definitions describe creativity as the combination of originality (novelty) and effectiveness (usefulness or value) (Runco & Jaeger, 2012). Domain knowledge, personality traits, and developmental factors also shape it.

Although creativity is considered vital for learning and development (Simonton, 2000), surprisingly few studies have explored whether watching films can enhance it.

One study found no difference in creativity between adults who watched a film and those who did not (Carbone et al., 2025). However, film viewers showed greater cognitive flexibility—the ability to shift between ideas—a skill closely linked to creativity (Diamond, 2013). Other studies have shown that cognitive flexibility supports original thinking and problem-solving (Zabelina & Robinson, 2010). Taken together, these findings raise new questions about what specific features of films might drive effects on creativity.

However, a lack of increased creativity in Carbone et al.’s experiment may be due to the film's focus on temporal complexity. Furthermore, the homogenous adult sample may also have masked significant differences. This leaves open the possibility that other film types, especially those with more imaginative or emotionally engaging content, might demonstrate stronger effects on creativity.

Grandville, J. J. (1844). A promenade through the sky [Illustration]. In Le Magasin pittoresque (June 1844). Wikimedia Commons.

The majority of previous research has focused on television rather than film, and the findings have been mixed.

This has led to two competing views:

Stimulation hypothesis

Audiovisual media boost thinking by engaging the senses (Laird, 1985; Valkenburg & van der Voort, 1994).Reduction hypothesis

Ready-made visuals reduce thinking (van der Voort & Valkenburg, 1994).

Despite these viewpoints, most earlier work examined television’s general effects without isolating specific features, such as fantasy. This is a notable omission, especially given how often both children and adults are exposed to fantasy content in screen media. To better understand the outcomes, it is important to look beyond broad effects and consider the unique role of fantasy.

Fantasy holds a special place in storytelling, offering experiences that stretch beyond the limits of the real world.

While realistic films follow the ordinary rules of everyday life (Hopkins & Weisberg, 2017), fantasy presents impossible events as believable. It invites viewers to suspend disbelief, imagine alternative realities, and engage in what if thinking. This genre encourages skills such as counterfactual reasoning—mentally exploring how things could be different—and the appreciation of complex, often symbolic worlds (Webster et al., 2025).

Baynes, T. M. (1833). Animated phenakistiscope disc – Running rats, Fantascope [GIF]. Wikimedia Commons.

Fantasy dominates children’s media (Taggart et al., 2019) and makes up nearly 30% of top-grossing films watched by adults (IMDb, n.d.).

Its popularity and emotional richness suggest that fantasy might influence how people think and learn. By transporting viewers into imaginative worlds that mirror or exaggerate real-life situations, fantasy can serve as a cognitive “playground” for creativity. For these reasons, its psychological effects across age groups warrant further research.

Fantasy’s popularity and its potential psychological effects across age groups form a compelling area for research. However, the literature so far presents a mixed picture, making further investigation especially valuable.

Some evidence suggests that encountering surprising or impossible elements can actually support learning. For example, Stahl and Feigenson (2017) found that preschoolers learned new words more effectively when the objects they saw violated real-world expectations. Yet other research points in the opposite direction. Rhodes et al. (2019) found that watching fantasy television temporarily reduced children’s working memory and cognitive flexibility, two abilities essential for creative thinking. Their study, however, did not control for differences in pace or language between shows, making the results difficult to interpret.

Similarly, Lillard et al. (2011, 2015) found no clear effect of fantasy cartoons on children’s creative problem-solving. In adults, results are equally complex: Black and Barnes (2021) found that viewers who felt deeply immersed in science fiction stories showed greater originality, suggesting that engagement, rather than genre alone, may drive creativity.

Horton, W. T. (1898). The path to the moon [Illustration]. In A book of images (California Digital Library collection).

Very little research has examined specifically how fantasy films affect adults’ creativity.

Some studies on children hint at potential benefits. Lin et al. (2013) found that watching a science fiction film increased technological creativity in adolescents, though they did not separate the film’s key fantasy features. Subbotsky et al. (2010) found that preschoolers who watched a magical clip produced more original and fluent ideas than those who watched a non-magical one. However, they did not account for factors like prior exposure or familiarity, which may have influenced engagement.

Overall, the evidence suggests that fantasy might spark creative thinking, but the mechanisms remain unclear. Whether fantasy enhances creativity or overwhelms it may depend on how the content is presented, the viewer’s age, and their level of engagement.

The effects of film on the mind don’t occur in isolation, but are mediated by other factors.

Several factors may mediate the relationship between film viewing and creativity. Understanding these mediating factors is essential for uncovering when and why fantasy might foster creativity. In the next sections, these influences are considered in detail.

How individuals respond to a story depends on who they are and how deeply they engage with it.

Traits such as openness to experience, a personality dimension linked to imagination and curiosity, are consistently associated with creativity (McCrae & Costa, 1997). People who score high on openness also tend to tolerate ambiguity more easily (Onraet et al., 2011) and show greater cognitive flexibility (DeYoung et al., 2005). Interestingly, openness also predicts broader film consumption and aesthetic appreciation (Carbone et al., 2025), although it remains unclear whether films cultivate openness or simply attract open-minded viewers.

Madame B. (ca. 1870s). From “Madame B Album” [Photograph]. Art Institute of Chicago.

Attempts to increase openness through art have produced mixed findings.

Reading fiction, for example, has been shown to boost empathy in some studies (Djikic et al., 2013) but not others (Wimmer et al., 2022). Likewise, Carbone et al. (2025) found no link between openness and creativity after participants watched artistic films. These inconsistencies may reflect the role of narrative transportation — the sense of being mentally absorbed in a story. Transportation involves focused attention, vivid imagery, and emotional engagement (Green & Brock, 2002; Green & Appel, 2024). When viewers feel fully “transported,” they experience a kind of temporary reality shift that may influence thought and emotion far more than passive viewing does.

White, J. H. (1973–1974). Artist Ron Blackburn painting an outdoor wall mural at the corner of 33rd and Giles [Photograph]. Documerica. Public Domain Image Archive / U.S. National Archives.

Finally, an individual's expertise level can mediate their engagement with film.

Film expertise is a viewer’s familiarity with cinematic techniques and artistic conventions. This expertise is often referred to as aesthetic fluency, which develops through varied exposure and an understanding of how film elements work together to create meaning (Smith & Smith, 2006; Silvia & Berg, 2011). However, most research on this topic has focused on adults. Little is known about how children develop film knowledge or how it might shape their creative thinking.

Screen exposure itself also matters. While excessive screen time has been linked to attention difficulties and slower language development (Anderson & Pempek, 2005; Swider-Cios et al., 2023), the quality of what is viewed can make a difference. For instance, Anderson et al. (2001) found that children who watched educational television in preschool showed higher creativity scores during adolescence. Yet studies like this rarely examine the role of fantasy within that content, despite its strong presence in children’s media.

Part Two: Aim & Hypotheses

The impact of fantasy films on creativity remains poorly understood. Previous research has mostly focused on television, often compared broad genres, and rarely included both adults and children. To address these gaps, this study tests whether watching fantasy versus realistic film excerpts influences creative performance across age groups. It also explores whether personality and other mediators explain any observed differences.

Specifically, we examined whether film expertise, openness to experience, and narrative transportation (the feeling of being absorbed in a story) predicted creativity after viewing a film excerpt.

Because children and adults differ in cognitive maturity and media experience, they were tested separately using age-appropriate procedures. Children aged 8–12 were chosen because they can follow complex narratives and use counterfactual reasoning (Rafetseder et al., 2013), making them well-suited to view the same film clips as adults.

_

Hypothesis 1.

Children and adults who watch either film clip will show higher creativity than those who do not any clip.

_

Hypothesis 2.

Participants who watch the fantasy clip will score higher on creativity than those who watch the reality clip.

_

Hypothesis 3.

Creativity will increase in line with film knowledge, openness to experience, and level of transportation.

Part Three: Methods

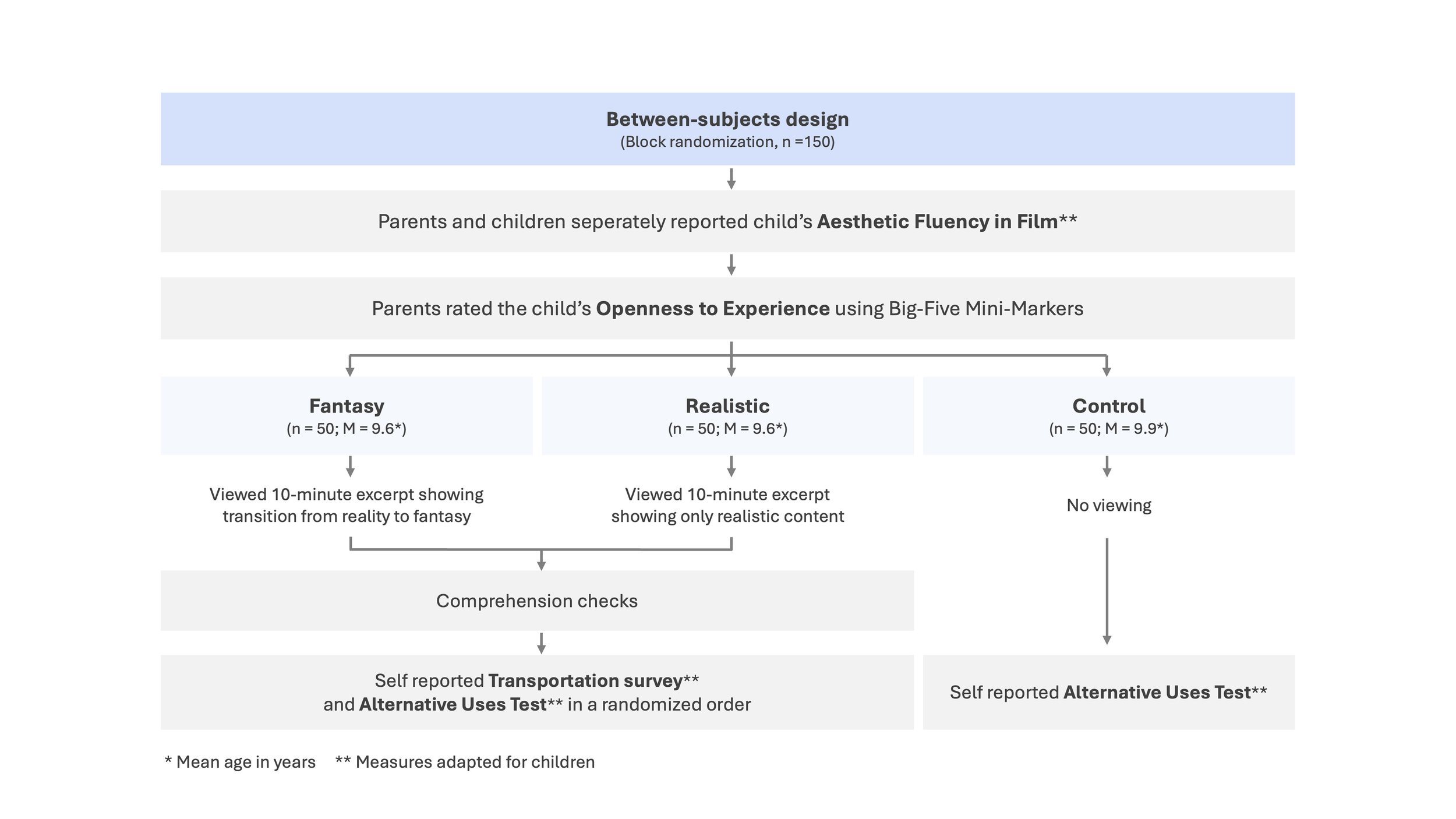

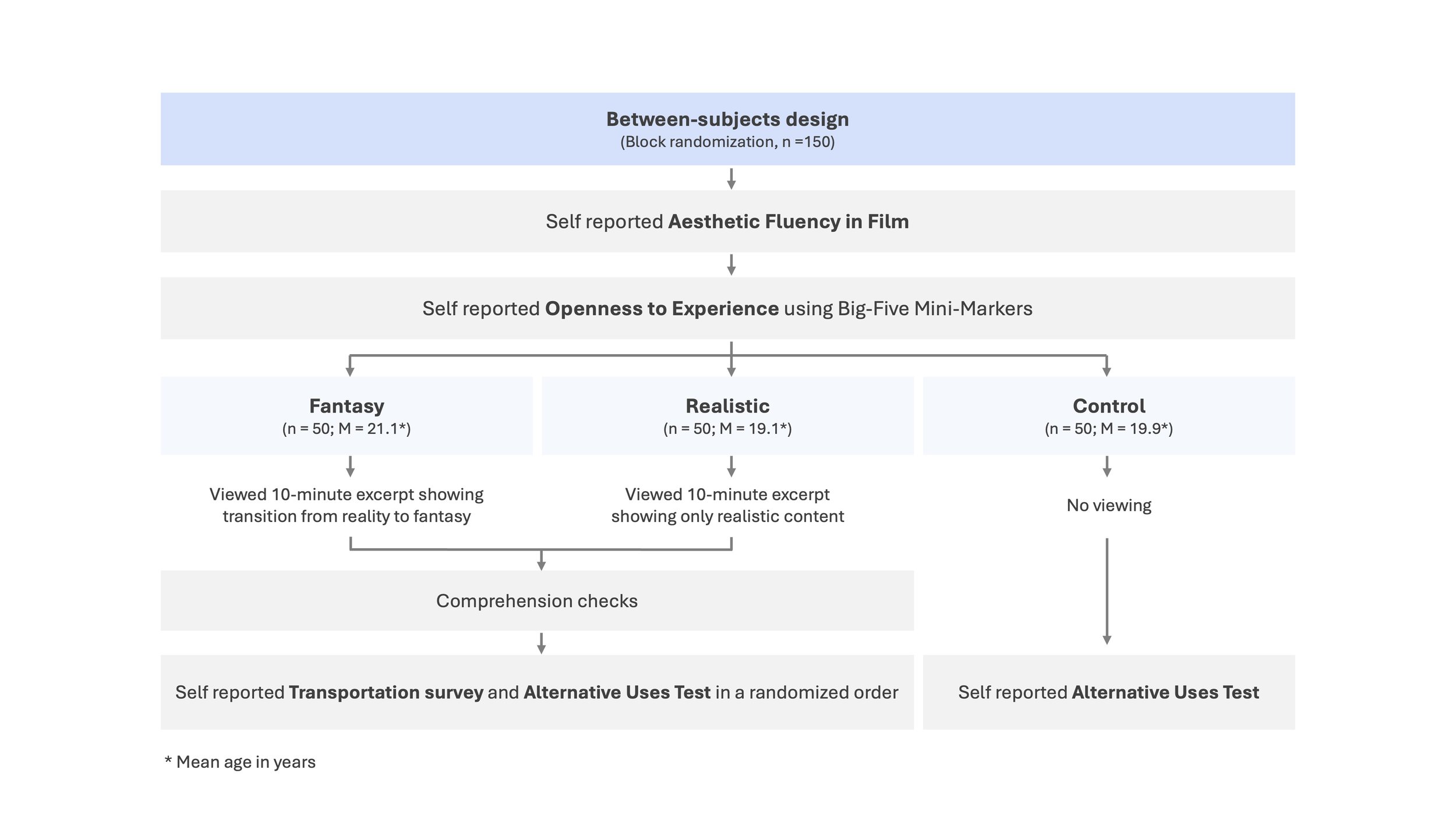

Design

In two separate experiments, we examined the effects of fantasy and realistic film excerpts on creativity. Both experiments used a between-subjects design with three conditions: fantasy film, reality film, and no-film control. Each participant was randomly assigned to one of these groups (N = 300; 150 adults + 150 children; 50 of each per condition).

Because of developmental differences, children and adults were tested and analysed separately.

Procedure

Experiment 1: Children

Experiment 2: Adults

Materials

All participants completed the study in a purpose-built testing booth in the laboratory at the University of Kent. (See image)

Film excerpts were selected from four critically acclaimed animated films, as indicated by their Rotten Tomatoes® Tomatometer scores (Rotten Tomatoes, 2025):

Coco (2017) = 97%

Soul (2020) = 95%

Luca (2021) = 91%

Turning Red (2022) = 95%

Outcome variable

Creativity was measured using the Alternative Uses Task (AUT; Guilford, 1967; George & Wiley, 2019), in which participants were asked to think of unusual uses for everyday objects (e.g., new ways to use a paperclip). Children were presented the AUT using a child-friendly version following Gaither et al. (2020).

AUT as presented for children:

AUT as presented for adults:

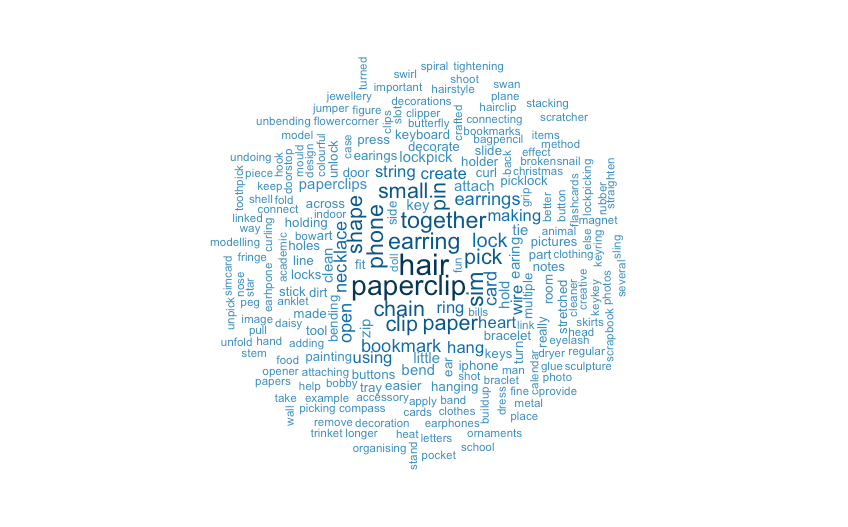

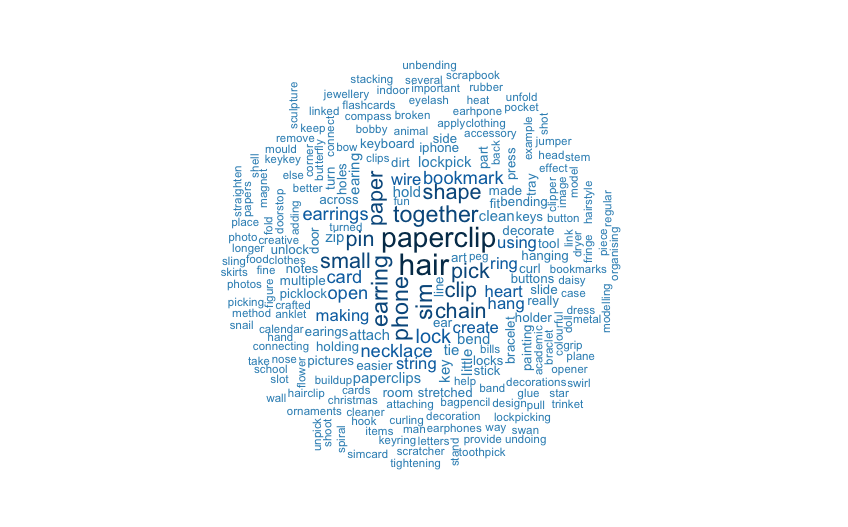

The word clouds below represent the most common responses generated by children and adults during the paperclip question of the AUT.

Children responses:

Adults’ responses:

Statistical analysis

All analyses were performed in R (Posit Team, 2025), and Helmert contrasts compared:

Both film conditions (fantasy and reality) versus the control (no film)

Fantasy versus reality conditions

Because most variables were non-normally distributed (Shapiro–Wilk ps < .001), generalised linear mixed-effects models with a Gamma distribution and identity link function were used. Condition was entered as a fixed effect, and participant ID as a random intercept. Predictor variables (film knowledge, openness, transportation, and age) were included as covariates.

To explore relationships among variables, Kendall’s Tau-b correlations were also calculated within the film conditions (α = .01).

Part Four: Results

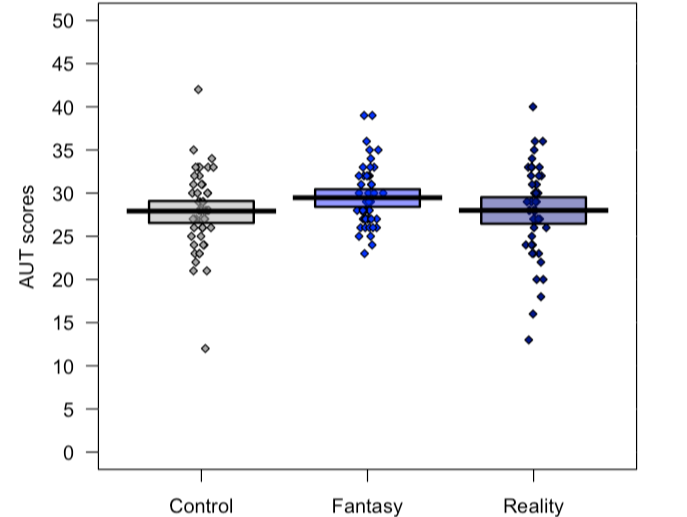

The box plot shows the effect of the condition on the creativity assessment task. It shows raw data points, a horizontal line reflecting the mean, and a rectangle around the mean representing the 95% Confidence Intervals.

Experiment 1: Children

Plot of children’s creativity scores

A visual inspection of the plot suggests slightly higher creativity scores among children in the no-film control group.

The GLMM confirmed this pattern, showing a significant effect of condition: children who did not watch a film were more creative than those who watched either a fantasy or reality.

Additionally, there was no difference between the fantasy and reality film groups.

Key finding

_

Watching any film clip (fantasy or reality) reduced children's creativity on the subsequent task.

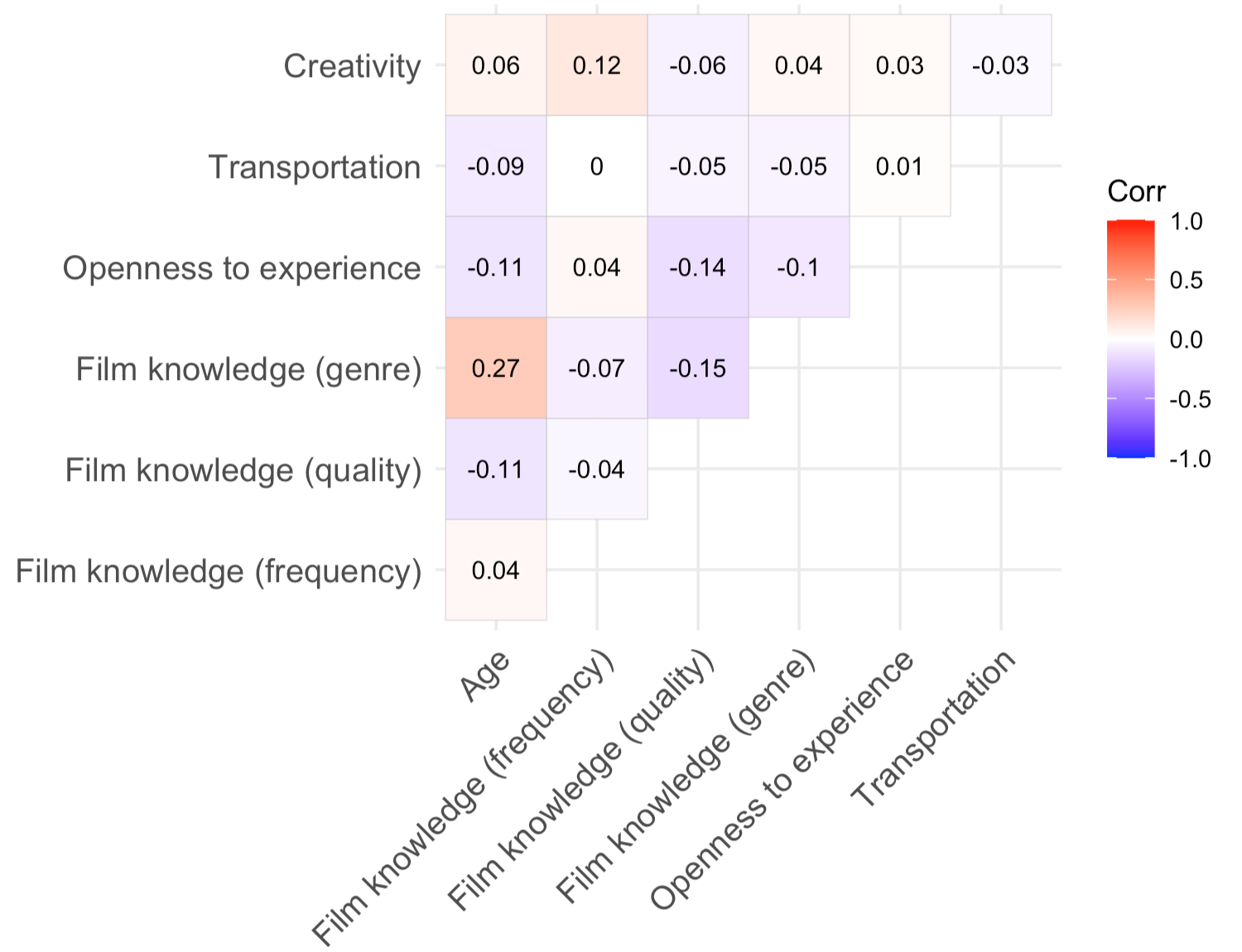

Correlation of children’s individual factors

To explore potential relationships among predictors, we ran Kendall’s Tau-b correlations within the two film watching conditions.

None of the predictors (film knowledge, openness to experience, transportation, or age) significantly predicted creativity in children.

However, a moderate positive correlation appeared between age and genre diversity, indicating that older children tended to watch a wider range of film genres.

Key finding

_

Personal traits like film knowledge, openness, and how absorbed children felt in the story did not explain their creativity scores.

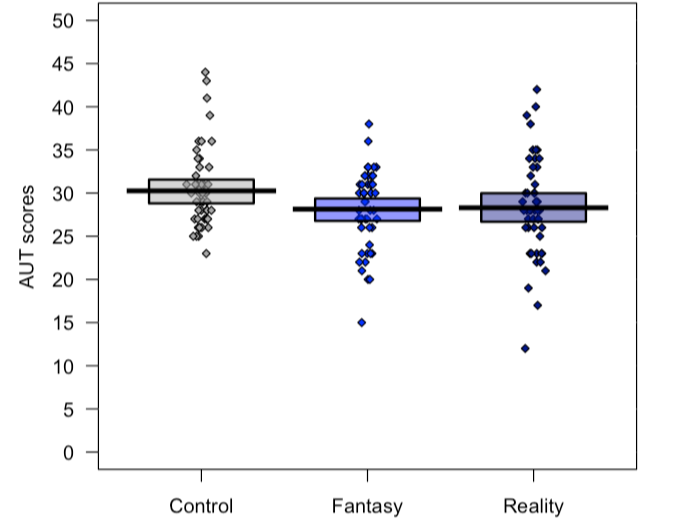

The box plot shows the effect of the condition on the creativity assessment task. It shows raw data points, a horizontal line reflecting the mean, and a rectangle around the mean representing the 95% Confidence Intervals.

Experiment 2: Adults

Plot of adults’ creativity scores

A visual inspection of creativity scores showed a slight trend toward higher means in the fantasy group, but the differences were small. The GLMM revealed no significant main effect of condition.

Key finding

_

Watching any film clip (fantasy or reality) had no effect on adults’ creativity compared with participants who watched no film.

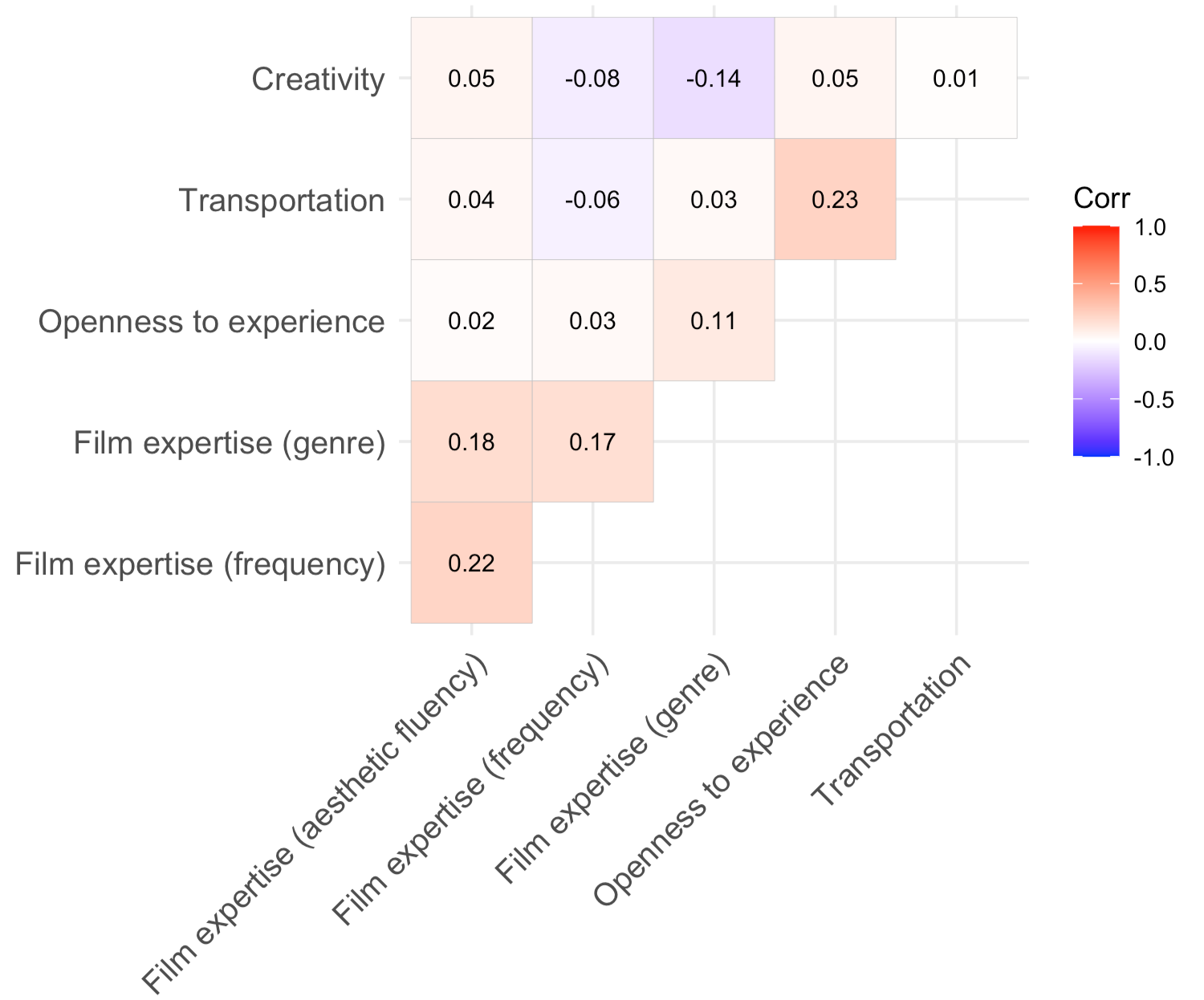

Correlation of adults’ individual factors

Creativity did not correlate significantly with any individual factors. However, two notable associations emerged:

Genre diversity correlated positively with aesthetic fluency, suggesting that adults who watched a wider variety of genres also tended to have greater cinematic knowledge.

Transportation correlated positively with openness to experience, indicating that more open individuals were more likely to feel immersed in the film.

Key finding

_

Like in Experiment 1, personal traits did not explain adults’ creativity scores.

The box plot shows the effect of the condition on the creativity assessment task. It shows raw data points, a horizontal line reflecting the mean, and a rectangle around the mean representing the 95% Confidence Intervals.

Experiment 2: Adults

Plot of adults’ creativity scores

A visual inspection of creativity scores showed a slight trend toward higher means in the fantasy group, but the differences were small. The GLMM revealed no significant main effect of condition.

Key finding

_

Watching any film clip (fantasy or reality) had no effect on adults’ creativity compared with participants who watched no film.

Correlation of adults’ individual factors

Creativity did not correlate significantly with any individual factors. However, two notable associations emerged:

Genre diversity correlated positively with aesthetic fluency, suggesting that adults who watched a wider variety of genres also tended to have greater cinematic knowledge.

Transportation correlated positively with openness to experience, indicating that more open individuals were more likely to feel immersed in the film.

Key finding

_

Like in Experiment 1, personal traits did not explain adults’ creativity scores.

Part Five: Discussion

In two experiments involving children and adults, our findings did not support our original hypotheses.

Watching a short film clip, whether fantasy or realistic, did not enhance creativity. In fact, children who watched any film clip were less creative than those who watched nothing, while adults showed no meaningful differences across conditions. Individual factors such as film knowledge, openness to experience, and narrative transportation also did not predict creativity.

Together, our findings suggest that brief film exposure, even when visually rich or imaginative, may not be enough to stimulate creative thinking. Below, we interpret these results in a developmental context and consider their theoretical and practical implications.

Watching a fantasy or reality film clip appears to have a negative effect on children’s creativity.

The finding that children produced less creative responses after viewing a film aligns with earlier work showing that television can sometimes dampen imagination (Valkenburg & Beentjes, 1997). This supports the reduction hypothesis (van der Voort & Valkenburg, 1994), which argues that ready-made visuals limit children’s own mental imagery. One possible explanation is that film viewing temporarily overloads attention.

According to capacity theory (Kahneman, 1973), the vivid colours, sound, and movement typical of animated films demand high cognitive resources, leaving fewer available for tasks that require internal generation of ideas. Since executive functions such as working memory and inhibition are crucial for divergent thinking (Diamond, 2013), this overload could reduce children’s creative output. But, as this was not directly measured in our experiment, this remains speculative.

Babbitt, E. D. (1878). Psychic lights and colors [Illustration]. In The principles of light and color. Public Domain Image Archive.

Interestingly, there was no difference between the fantasy and reality conditions, suggesting that fantasy’s imaginative elements did not offer additional stimulation for children.

This contrasts with studies reporting gains in creativity following exposure to magical or science fiction content (Subbotsky et al., 2010; Lin et al., 2013). However, those studies involved older children and longer interventions that allowed time for reflection and learning. In contrast, the brief exposure used here may not have been sufficient for fantasy to take effect. From a sociocultural perspective (Vygotsky, 1978), creativity develops through social interaction, play, and internalisation — processes that a short, passive viewing experience cannot easily support.

Developmental differences may explain the null effects.

Creativity does not increase linearly with age but fluctuates across childhood, often peaking and dipping at different stages (Barbot et al., 2016). A meta-analysis by Said-Metwaly et al. (2021) identified a plateau in divergent thinking around ages 9–10 and a temporary decline around 12 years, which overlaps with the age range tested here. Such “creativity slumps” could mask potential benefits of fantasy exposure.

While no strong correlations emerged between creativity and individual factors, older children tended to engage with a wider range of genres.

This pattern may reflect increasing curiosity and comprehension with age (Valkenburg & Piotrowski, 2017). Though speculative, it hints that media diversity, not just amount, may play a subtle role in creative development.

Among adults, creativity scores did not differ between groups, mirroring previous research showing that short-term film viewing failed to enhance divergent thinking (Carbone et al., 2025).

One possible explanation is that adults’ existing cognitive frameworks are already well established, leaving little room for brief media exposure to influence creative performance.

From a dual-process perspective, creativity depends on a flexible balance between divergent (idea generation) and convergent (idea evaluation) thinking (Sowden et al., 2015). Because participants were asked to produce only one creative response per item, the task may have emphasised evaluation over exploration, reducing the opportunity to express divergent thinking.

Babbitt, E. D. (1878). The psycho-magnetic curves [Illustration]. In The principles of light and color. Smithsonian Libraries and Archives

Although there was no measurable impact of fantasy, a small, non-significant trend toward higher creativity in the fantasy condition suggests that imaginative content could have subtle effects under different circumstances.

For instance, prior work by Black and Barnes (2021) found that narrative immersion in science fiction predicted greater originality, implying that engagement, rather than genre, drives creative benefits.

In our study, transportation scores were modest and did not differ between fantasy and reality clips, suggesting that the excerpts may not have been immersive enough to elicit measurable changes in thinking.

It is also possible that our sample’s homogeneity limited variability.

University students often share similar educational backgrounds and cultural references, which can narrow creative diversity (Marozzo et al., 2024). Additionally, creativity is shaped by long-term habits of curiosity and openness—traits unlikely to shift after a single viewing session.

Correlations between genre diversity and aesthetic fluency, and between transportation and openness, further support this interpretation. Individuals who consume a broader range of media and who are naturally open to experience tend to engage more deeply with stories. However, such engagement alone may not translate into immediate creative performance.

Our findings challenge the stimulation hypothesis, which assumes that audiovisual media enhance cognition by stimulating the senses and emotions.

In the short term, passive film viewing does not appear to increase creativity and may even suppress it in children. This suggests that creativity does not arise simply from exposure to novelty or sensory richness but from active engagement — a process that may require time, reflection, and interaction.

For educators and practitioners, this has practical implications.

Short film clips, even high-quality ones, should not be relied on as quick tools to boost creativity. Instead, activities that encourage discussion, imagination, and reinterpretation of film content may be more effective.

At a theoretical level, the results highlight the importance of distinguishing between creative potential and creative performance (Walia, 2019). It remains possible that participants’ divergent thinking was momentarily activated but not captured by our output-based measure. Future work could use process-oriented tasks or longitudinal designs to track changes in creativity over time, perhaps combining behavioural tasks with physiological or neurocognitive measures.

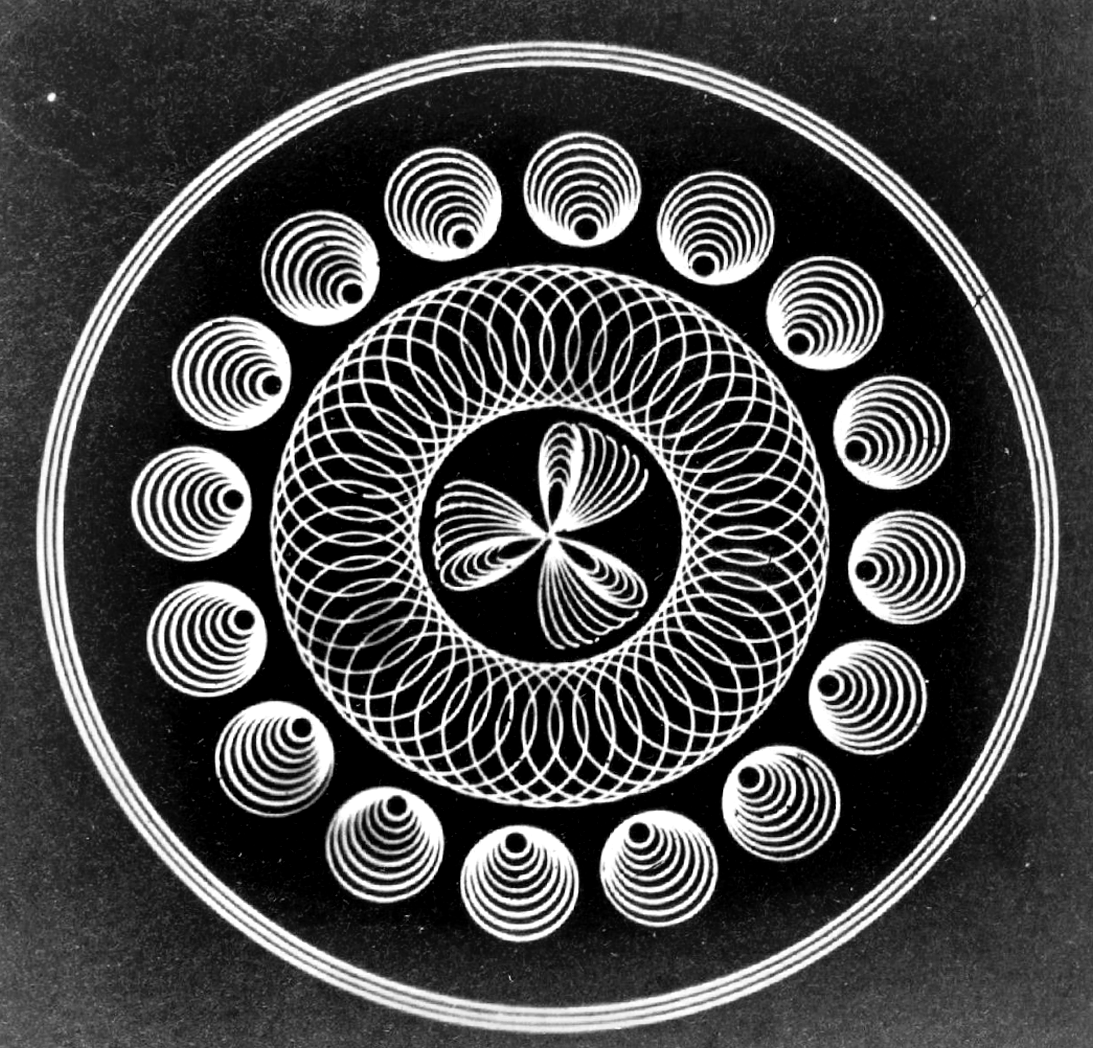

Woolsey, E. J. (1869). Specimens of fancy turning [Wood engravings]. Philadelphia Museum of Art.

Future studies on creativity and film should also address several limitations identified in our study.

The AUT, while widely validated, measures only one aspect of creativity and may overlook more applied or socially relevant forms (Sternberg & Grigorenko, 2000; Erwin et al., 2022). Scoring can also be subjective and biased toward utilitarian answers rather than personally meaningful ones. Furthermore, our reliance on animated Disney-Pixar clips, while controlled for quality and familiarity, may have obscured differences between fantasy and reality conditions due to their shared aesthetic style.

Viewing habits are rapidly changing and our study did not take this into account.

According to Ofcom (2025), YouTube is now the most common platform among children aged 4–15 and the second most popular among adults aged 16–34. With the rise of short-form, interactive, and user-generated content, future research should examine how these new media formats influence creative thinking across development.